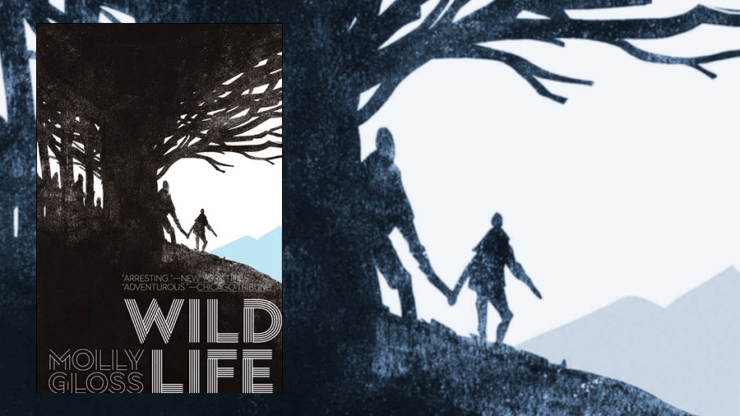

Set in the Pacific Northwest at the turn of the twentieth century, Wild Life takes the narrative frame of a journal, written across a period of weeks, by Charlotte Bridger Drummond—single mother of five boys, ardent public feminist, professional adventure-romance writer—wherein she has a wilderness experience of her own. Her housekeeper’s granddaughter has gone missing on a trip with her father to the logging camp where he works. Charlotte, repulsed by the company of men but functional within it, takes it upon herself to join the search, as the housekeeper is too old and the mother too frail. At once a work of historical fiction, a speculative romance in the traditional sense, and a broader feminist commentary on genre fiction, Gloss’s novel is a subtle and thorough piece of art.

Originally published in 2000, almost twenty years ago, Wild Life is nonetheless recent enough to have a digital trail of reviews in genre spaces. A brief search reveals a contemporaneous essay at Strange Horizons, one from Jo Walton here at Tor.com in 2010, and more. For me, though, this was a first read—as I suspect it will be for many others—and I’ll approach it as such. Saga’s new editions of Gloss’s previous novels are a significant boon to an audience unfamiliar, like myself, with her longform work.

The title of the novel works the wonders of the book in miniature: readable as “wildlife,” flora and fauna, the “wild-life” as in unrestrained frontier living, and “wild life” in reflection on the unpredictable weirdness of being. The angle of approach changes the angle of engagement with this multifaceted, precise, and immensely vibrant text. The book is framed first via a short letter from one sibling to another, an explanation of the journal written by their grandmother that she’s found in their father’s things—and whether it’s true or fictional, Charlotte’s recounting of the events of 1905 are offered up as potential fodder to the other grandchild, who is a scholar of her work.

However, from the moment Charlotte’s journal begins the novel proper, I was hard pressed to remember I was reading a piece of fiction published at the start of the twenty-first century. Having spent a fair share of my time in academia reading pulp dime novels and adventure stories, that early speculative work Gloss is in conversation with here, I’m impossibly impressed by the spot-on perfection of the prose in this book. Charlotte’s voice is so well-observed, so crafted, that it reads as natural as breathing. The Pacific Northwest comes to life on each and every page, almost to the smell. Again, there were split moments I genuinely forgot this was a historical novel. There’s no higher praise for the recreated tone and diction of a prior period of writing in a contemporary book.

Gloss, though, is also engaged in commentary on the genre and social climate she’s exploring—not content to rest on simple imitation. Wild Life is itself a romantic adventure, but it’s simultaneously about romantic adventure books—an author writing an author writing. Charlotte is humanely imperfect and often blissfully direct as a narrator. For example: She is a feminist who is cognizant of the strains of single motherhood on her time, as well as the questions of class that lead her to employ a housekeeper rather than sacrifice her life to her sons though she loves them dearly. She is also on occasion cruel in her coldness, prone to judgments of others, and an intentional product of her time. Gloss does a masterful job balancing the progressive politics of 1905 against our contemporary understanding of the shortcomings therein. Charlotte is critical of the expansion of white men into the primeval forests; she also presents most men, both in her fiction and in her journal, as immature monsters unwilling or unable to give a damn about other people.

But, at the same time, her professed respect for native peoples is tinged with period typical well-meaning racism—Gloss doesn’t avoid this. Charlotte’s narratives of gentle “savages” and romances involving a plucky white woman swept up by and ultimately becoming a respected leader in a local tribe smack of a brand of paternalistic white feminism that deserves our interrogation—and it’s not as if white American culture has moved much past that stage, even today. There is another, similar moment in the text regarding queerness that puts Gloss’s brand of intentionality front and center: Charlotte admits her discomfort with Grace to herself, because even though she supports the idea of a liberal west, she is uncomfortable with the thought that a woman might express a sexual interest in her. She knows it’s wrong of her to think so, yet does think it, and then thinks about that too. It’s a delicate balance to strike, representation and criticism in the same turn of phrase. It requires the audience to read carefully and slowly, to consider the layers of the frame and the layers of Gloss’s project at the same time.

The work of careful reading, though, pays off. Particularly given that Wild Life is a novel aware of its place in a tradition of novels about “wild men of the woods”—in this case, the sasquatch. Charlotte, lost in the woods after a sexual assault by one of the men in the camp and a subsequent fright, is near to starving. She’s unable to locate herself geographically and falls incrementally into the social company of a familial band of sasquatches: mother, older child, twin young children. She is the strange orphan they adopt; she learns their language, lives wild as they live, still journals but does not speak. In their company, she witnesses the virulent brutality of white settlers from an entirely different, visceral, physical perspective—what was academic before becomes life and death. She experiences that which she theorized.

Though in the end she is returned via happenstance to society, to her family and the soft-spoken farmer who’s been courting her over years and years, she is not the same person following her experience. The majority of the novel is a purely realist historical journal, an exploration of frontier feminisms and early-century progressivism that is on another level also a genre commentary by Gloss, but the latter third is the powerhouse of the piece. The integration out of and then back into the social order, the effects of trauma and bonding, of seeing outside one’s own narrative to the experience of others—truly, truly experiencing that life—is a fracture. For Charlotte, it is the kind of fracture that allows the light to come in. One of the most moving lines of the novel occurs after a frontiersman murders and field-dresses one of the twin child sasquatches. In mourning, Charlotte writes:

The mother of the dead child looks out at the country with a stunned expression, as if the world has been made desolate and hostile, as if she has been set down suddenly among the rocky craters of the moon. She does not speak. I think I must be writing for both of us—writing as women have always written—to make sense of what the heart cannot take in all at once. (250)

Buy the Book

Wild Life

Writing as women have always written. That line is another key to the project of Wild Life. Gloss has constructed a tale that grips on its own merit, emotionally and psychologically; a very human piece of fiction that breathes its time and place to the reader across each word. However, she has also written an eloquent treatise on the functions of pulp fiction and women’s experiences of oppression. Charlotte is a political firebrand; she is also a mother, a writer, a person who bonds with the wild other-humans of the woods. Her complex identities play off of each other. She grows and changes through her experience as it brings her closer to the interior of her being, separate from social roles and expectations that she must act either in favor of or against, separate from the racialized and gendered world she has known. She is in it and of it, but her return—that is where the door is left open to more radical progressive changes.

The last pages of the book are a selection from one of Charlotte’s latter short stories. The story is told from the perspective of the sasquatch peoples on the arrival of white settlers, initially unsure of their intentions but increasingly alarmed by their disrespect for the land and their unrepentant violence. This closing piece is wildly different from the unpublished draft of the earlier and more period-typically racist “Tatoosh” story Charlotte was writing at the start of the book, where a fainting adventuress meets gentle native beasts and is taken to their city, et cetera. The shift in perspective makes direct the shift in her empathetic and sympathetic understandings after her experience, a significant break from the expected as her approach to her feminism and social order has also evolved. It’s a quiet, subtle thing, but it’s the knot that ties off the thematic arc of the novel.

Wild Life is a fantastic book, rich and intensely self-aware. It’s referential without being pedantic, philosophical but narratively engaging. Charlotte is a narrator whose good intentions leave her room to grow through experience, through trauma, through broadening her horizons and her sense of what human is or could be. As a historical it’s utterly divine from tip to tail; as a bit of metafiction it’s crunchy and thorough; as a feminist reimagining of those old “wild man” novels from within the perspective of the period when it’s set it offers a complex view of progressive politics falling short and shooting long at the same time. Wild Life isn’t a simple novel, though it has things to say about simplicity, and it’s doing a great deal—very much worth settling in with for a long weekend’s perusal.

Wild Life is available from Saga Press.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.